The following examples demonstrate the different ways people have addressed extractivism in their communities. Please give them prayerful reflection and consideration and identify common themes, gaps of possible responses, and those which resonate with you.

- Legal Intervention

- Accompaniment and Solidarity — Panama

- Accompaniment and Solidarity — the Philippines

- Creative Protests

- Advocacy Through Shareholder Pressure

- Persistent Mass Mobilization

- Corporate Voice and Solidarity

- Listening Sessions For Recommendations

- Iglesias y Mineria – Churches and Mining Divestment Campaign

1.) LEGAL INTERVENTION

“Rural Peruvian community of Condoraque begins to see fruits of its labor, after years of advocacy” by Maria Pia-Negro Chin, photos by Nile Sprague (Reprinted with permission from Maryknoll Magazine, July 2017)

Villagers call the Condoraque River “burning waters” because the toxic waste coming from the mine upstream made the river untouchable. The once life-giving river in rural Puno, Peru, was devoid of life to the point that the Aymara Indigenous people of the village wondered how they would survive next to such a contaminated water source.

But after nearly seven years of working with the Human Rights and the Environment (DHUMA), a Maryknoll-supported nonprofit organization in Peru, the mine has finally launched a plan to restore the Condoraque to health.

Ubaldo Layme Gil, past president of Condoraque village, says residents persisted to have their voices heard. As first reported by Maryknoll magazine in 2010, about 50 Aymara families saw their water contaminated by tons of toxic tailings from a tungsten mine that opened near their community in the 1970s. The Indigenous people of Condoraque were not consulted before mining operations began, and when the original mining company left in the 1990s, it did not restore the damages it caused.

A second mining company later began operations in the area on the condition that it repair the environmental damage caused by the first mine. But the new company began mining without rehabilitating the area.

Realizing the new mining company was failing to fulfill its responsibilities to clear up the contamination, Condoraque community leaders invited DHUMA representatives to see what the toxic mine waste was doing to the people, their livestock and their property.

After other authorities ignored their plight, Simon Orihuela, a former community president, asked Maryknoll Sister Patricia Ryan, DHUMA’s president, and her team to “come and see” what the mine’s toxic waste was doing to the village and how the contaminated water was making their livestock sick and causing their alpacas to abort their calves.

“Once you go and see, you are totally convinced of the gravity of the situation,” says Sister Ryan, who as a Maryknoll missioner in Peru puts Catholic social teachings into action by advocating for social justice and care for the environment. “Since then, we have been working together with the community in monitoring the water and working on a penal case (to hold the mine responsible for the cleanup of the environmental contamination).”

Thanks to these efforts, mine officials have accepted their responsibility and launched a five-year plan to rehabilitate the environment of Condoraque. An integral part of this plan is the remediation of environmental liabilities, including dealing with more than 1. 2 million metric tons of toxic tailings and continuous acid drainage from the mineshaft, and the severe contamination of a natural lagoon between the mine and the river.

Although it still has an orange tint, the Condoraque River is slightly cleaner now because of channels dug to capture rainwater at the top of the mountains and transport it to the river in pipes to circumvent the toxic tailings below. Orihuela and Layme are still concerned that the water quality is not as healthy as it should be.

“It is going to take at least five years for the water to be restored to usable purposes,” Sister Ryan estimates and then adds, “There is still a lot of contamination.”

However, the beginning of remediation marks a victory for the village.

“We are very pleased by what we are seeing because the main objective of the people of Condoraque is that the environment be restored. as it had been before,” says Sister Patricia Ryan. “That their water is going to be drinkable … and that there would be birds and fish again and no more disease.”

2.) ACCOMPANIMENT AND SOLIDARITY — PANAMA

Written by Extractives Theological Reflection Working Group

Sister Edia “Tita” Lopez has been accompanying the Ngäbe communities of Chiriquí Province, Panama, for the past 12 years. She worked in solidarity with the Ngäbe as they struggled unsuccessfully to resist the Barro Blanco hydroelectric dam, and she continues to be present with them sincethey were evicted from their land. She expresses that her solidarity is rooted in the Gospel of Matthew 25: “As often as you do it for one of the least of these, you do it for me”; Pope Francis’ call to social friendship in Fratelli Tutti; and the Sisters of Mercy’s 2017 Chapter Recommitment, “Called to New Consciousness.”

Tita began and continues her solidarity with the people because they are the most impoverished, excluded and forgotten people in her country. She visited every 15 days, and now visits whenever they call on her to hear their stories and offer support.

She asks herself: How can I be in solidarity with them and do something to alleviate their pain and suffering? How can we change the reality of discrimination and racism that our Ngäbe brothers and sisters live with in the country? How can we act in solidarity for a just world?

Tita learned firsthand the impacts of the massive hydro project on the land and the communities of the Ngäbe. One of the Ngäbe communities, evicted from its land, continues to live as a resistance camp along a major highway. They face tremendous difficulties.

The Ngäbe communities had depended on the Tabasura river when it flowed generously through their lands, but the river is no longer freely flowing, and in certain seasons it dries up completely. Agriculture and fishing have declined. The GENISA company introduced tilapia, a non-native species of fish, and that has affected the river’s ecosystem. The Ngäbe suffer perpetual stomach problems and other ailments due to deteriorated water quality. Women of the Ngäbe communities must walk for hours to access clean water in order to cook, wash their clothes and do other household chores. Children and young people can no longer play in the river. The quality of life in the communities has been greatly diminished, and the environmental, social, and economic damage has increased exponentially. The communities suffer severe economic shortages, and their customs, traditions, livelihoods and whole way of life has been impacted.

Tita and others who have seen the devastating effects of the hydroelectric plant have joined with the Ngäbe communities in speaking with the authorities and trying to raise awareness of the plight of the Tabasara River. She documents the people’s experiences and contrasts these reports with those of the authorities to determine how their human rights are being violated. These reports will be used in a pending hearing before the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights. In addition, these reports have been given to investors involved in the dam project. These investors are now determining how to make a “responsible” exit.

3.) ACCOMPANIMENT AND SOLIDARITY — THE PHILIPPINES

Missionary Sisters of St. Columban in the Philippines built on three decades of relationships with the Subanen people [a group Indigenous to the Zamboanga peninsula area, mainly living in the mountainous areas of Zamboanga del Sur and Misamis Occidental, Mindanao Island, Philippines] to support a successful campaign against mining in the community.

The sisters came to appreciate the Indigenous people’s traditional values centered in interconnectedness with Mother Nature. However, they lamented the encroachment of consumerism and practices such as fertilizers that damaged the land.

Sister Anne Carbon explains that the sisters’ long-term presence and understanding of traditional culture gained them the trust needed to counter pressure from local government and the Rio Tinto corporation seeking approval to mine in the area.

Over 15 years, while the government and the corporation tried to sway the local people with money and promises of benefits from the mines, the sisters educated them about their rights, supported petitions and letter-writing efforts, and even visited Rio Tinto’s offices in London. The key to the eventual success in convincing governmental officials to reject the mining proposal was carefully reviewing the corporation’s applications and identifying where similar promises to other communities were never fulfilled. The sisters and the people visited those communities and saw the diseases afflicting those living near mines and the pollution of water sources.

Sister Anne says that connecting with others seeking dignity for Indigenous peoples and protecting the environment is also critical. Sisters and priests working with Indigenous peoples in the Philippines, for instance, meet monthly to support one another in their ministries. And representatives from Indigenous groups from throughout the country meet at least once a year.

4.) CREATIVE PROTESTS

Written by Marianne Comfort, Mercy Justice Team

In the summer of 2017, the Transcontinental Gas Pipeline Corporation used eminent domain to seize land from the Adorers of the Blood of Christ in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, to extend its Atlantic Sunrise natural gas pipeline.

The sisters felt strongly that this violated the land ethic they had adopted in 2005. They had committed to honoring the sacredness of all creation, kinship with all living beings, reverencing Earth as a sanctuary and treasuring land as a gift of beauty and sustenance. They also stated that they “seek collaborators to help implement land-use policies and practices that are in harmony with our bioregions and ecosystem.”

The Adorers joined the grassroots coalition Lancaster Against Pipelines and agreed to install a chapel on their property to draw people to prayer and reflection about just and holy uses of land. The sisters believed that the chapel gave a tangible witness to the sacredness of Earth. At the same time, they challenged the pipeline’s construction as a violation of their deeply held religious beliefs around stewardship of the environment.

The sisters lost a series of lawsuits.The pipeline was completed in 2018 and now carryies natural gas from the Marcellus Shale of northeastern Pennsylvania to the Mid-Atlantic and southeastern regions of the U.S. But their witness inspired many others.

By Pat Zerega, Senior Shareholder Advocacy Director of Mercy Investment Services

After seeing mountaintop removal in West Virginia and the explosion of fracking wells in southwestern Pennsylvania while living in those areas, I thought I was prepared to experience mining in Central America. But my first visit to a gold mine in Peru in 2012 was eye-opening. The enormity of the project –– stripping miles of land and going deep into the Earth, making the giant trucks look like tinker toys –– took my breath away. During meetings with community groups, my heart broke as I heard from residents who lost relatives in the struggle and whose communities and livelihoods were forever changed. That first visit ignited my passion to address the human and environmental impacts of mining.

In 2014, after hearing from Sisters in Honduras, the Institute Justice Office contacted Mercy Investment Services to determine how shareholder engagement could effectively complement other ongoing advocacy efforts seeking to address the social and environmental impacts of Aura Minerals, a Canadian mining company operating a gold mine in Honduras. Because Mercy Investment Services did not own any shares, we intentionally purchased five hundred dollars in company stock strictly to influence their decisions through engagement. I connected with the Jesuit Committee on Investment Responsibility, which had been engaging Aura to develop a human rights policy, and they welcomed Mercy Investment Services’ participation. At an in-person meeting with the company, Mercy Investment Services and the Jesuit team shared what an exemplary human rights policy contains, emphasizing the inclusion of Free, Prior, Informed Consent (FPIC) and identifying and addressing the company’s salient human rights risks. In 2016, shareholders and Aura management discussed the company’s plan to move the Azacualpa cemetery, and shareholders implored the company to address the community’s concern.

Meeting with the company on behalf of the sisters and impacted communities is a privilege and a huge responsibility. We present the lived stories of affected people, having a unique entree at top levels of the corporation. I met with Aura’s past and current Chief Executive Officers, who listened intently to shareholders’ call for a new approach to human rights. As a first step, we requested that Aura create a company-wide policy to adopt and train all employees in FPIC.

After years of discussions and many leadership changes, the company agreed to this approach. In 2021, Aura’s board of directors approved a new Human Rights policy, which is available on the Aura website in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. It covers many of the original points requested, including reference to United Nations norms, FPIC, a call for a human rights analysis and implementation through its business partners. Shareholders shared this policy with local community contacts to engage the company on their concerns, including those around the cemetery.

Mercy Investment Services will continue to stay engaged with Aura to ensure that it implements the policy to address community concerns and with local groups to continue to bring their voices to the company. My work in shareholder engagement to combat human rights and environmental impacts at Aura and other extractive companies complements the Sisters of Mercy’s discussions and community actions, investment choices, legal actions, and, most importantly, personal consumption decisions as we collectively seek justice, equity and peace for impacted communities.

6.) PERSISTENT MASS MOBILIZATION

Written by Marianne Comfort, Mercy Justice Team

Since 2008, the Sioux and other Indigenous peoples in Nebraska, Montana, North Dakota and South Dakota have resisted the placement of the Keystone XL Pipeline through traditional homelands and treaty territories. They feared potential impacts on their fishing and hunting rights, water systems and cultural sites.

The pipeline, to be built by the TransCanada (TC Energy) corporation, was to carry oil from heavy tar sands in Alberta, Canada, down to the U.S. Gulf Coast. Native-led mass mobilization and court proceedings fueled a strong international response. They raised public awareness of the dangers of a fossil fuel economy and the call to enable kinship and the flourishing of the community of life.

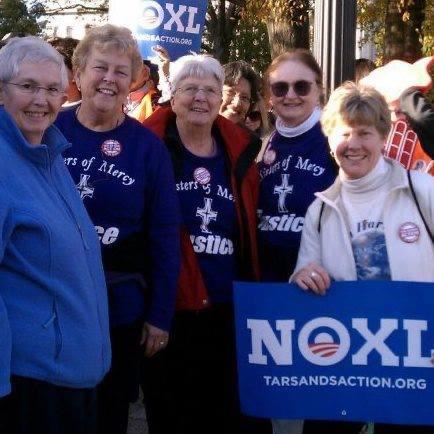

Rallies, marches, and large waves of civil disobedience in Washington, D.C., drew environmentalists, students, people of faith and, in one particularly compelling demonstration, solidarity between ranchers and Indigenous communities from Nebraska. There was also strong opposition at public hearings in states along the proposed route of the transnational pipeline. Four years after Mercy sisters and coworkers joined the first large protest at the White House in 2011, President Obama announced that he was rejecting the pipeline proposal. The Trump Administration tried to move the pipeline forward again, but ongoing lawsuits in Nebraska delayed construction. President Biden canceled the permit on his first day in office. The pipeline sponsor, TC Energy, announced in June 2021 that it was giving up on the project.

7.) CORPORATE VOICE AND SOLIDARITY

Written by Extractives Theological Reflection Working Group

Leading up to the COP26 climate talks in Glasgow, Scotland, the religious conference for women and men religious in Brazil reached out to the Leadership Conference of Women Religious in the U.S. to explain their deep concern for the Amazon rainforest and its peoples.

Sister Carol Zinn, LCWR’s executive director, promptly wrote a letter to President Biden and the White House and State Department staff. It reads, in part: “We stand in solidarity with the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil knowing there is no future for the Brazilian Amazon or planet Earth without protecting the rights to land, health, and culture of those who have cared for this precious ecosystem for millennia.” The letter asked that the Biden administration support Indigenous leaders’ call for protecting 80 percent of the Amazon rainforest by 2025 and called for the protection of the human rights of Indigenous leaders, who were criminalized for defending their land and way of life.

8.) LISTENING SESSIONS FOR RECOMMENDATIONS

Written by Marianne Comfort, Mercy Justice Team

Church leaders invited peoples of the Amazon rainforest to give input in advance of the Amazon Synod, a high-level Church meeting held at the Vatican in October 2019. The Synod was called to identify new pastoral approaches and ways of supporting communities threatened by extractivism, deforestation, climate change and human rights abuses.

Mercy Sister Denise Lyttle of Guyana attended one of many listening sessions hosted by dioceses, parishes and organizations throughout the nine-country territory.

“There, I learned that our Amazon needs to be cared for by all, not just by those who live in the Amazon,” Sister Denise wrote in a reflection soon after the experience. “As someone said, ‘the pain and groans of our people are the groans of our Mother Earth’ who is calling us to be more conscious and more responsible in caring for the ‘lung’ of our world, on which depends our life and that of future generations.”

Mercy sisters, associates, ministry colleagues and friends also participated in two discussions with representatives from REPAM, a Catholic Church network that promotes the rights and dignity of people living in the Amazon. These conversations, through the lens of Laudato Si’, touched on many issues and concerns, including land titles for Indigenous people for lands that they have occupied for generations, water pollution from both garbage in the city and gold mining in the interior regions, corruption, the need for a spirituality that meets the people, the impact of deforestation, and the benefits and challenges of finding oil in Guyana.

This and other input from throughout the Amazon was compiled into a preliminary report to serve as a basis for the meetings at the Vatican.

In an unusual move, delegations to the Synod included Indigenous leaders (men and women) amid the expected bishops and cardinals. Pope Francis’ affirmation of the Synod’s final document included quotes from poets of the Amazon and a deep sense of the interconnectedness of creation found in Indigenous spirituality.

As one outcome of the Synod, in June 2020, Catholic leaders created the Ecclesial Conference of the Amazon to help implement the recommendations. The conference’s executive committee is composed of the heads of church bodies in Latin America and three Indigenous leaders.

9.) IGLESIAS Y MINERIA – CHURCHES AND MINING DIVESTMENT CAMPAIGN

Written by Extractives Theological Reflection Working Group

In August 2019, Mercy Sister Anamaria Siufi of Argentina participated in the fourth general assembly of Iglesias y Mineria (Churches and Mining). This network of Christian communities, pastoral teams, religious congregations, theological reflection groups, bishops, pastors, and laity seeks to respond to the violations of rights caused by mining activities in Latin America. They also aim to strengthen popular movements and sectors, democratic values, gender equality, respect for multiculturalism, interculturalism and interreligious dialogue and ecumenism.

At the general assembly, the deaths of 272 people in a collapse of a dam used by the Vale mining corporation in Brumadinho, Brazil, weighed heavily on participants’ minds. Ana shared in a reflection afterward:. “The harrowing testimony of that diocese’s bishop along with other heartbroken people from that area moved us, and we shared their tears, which became a prayer and Eucharist,” she wrote.

One of the priorities that came out of that assembly was a campaign to promote divestment from mining companies in the Global North.

Fr. Dario Bossi of Iglesias y Mineria presented this campaign at a workshop co-hosted by the Mercy Justice Team at Ecumenical Advocacy Days in April 2021.

The campaign is designed to show the realities of extractivism in Latin America, dispute the positive image that corporations try to portray of their contributions to local communities, and build alliances. Organizers want organizations to understand that they may be investing in corporations damaging the environment and communities. And they want to propose alternatives for more socially and environmentally responsible investments and forms of development that are sustainable and focus on the autonomy of local communities. This includes supporting local or regional economies and financial systems, such as cooperatives.